September 19, 2025

The Bob Mizer Foundation: new name, same mission; preserving physique erotica

Jim Provenzano READ TIME: 1 MIN.

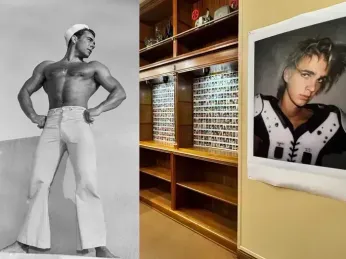

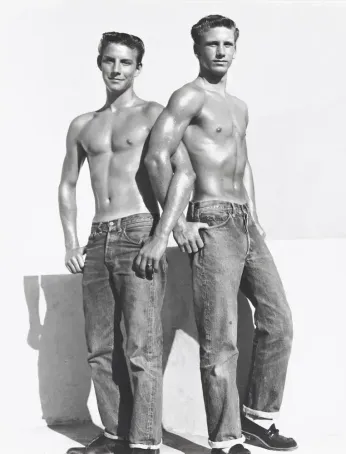

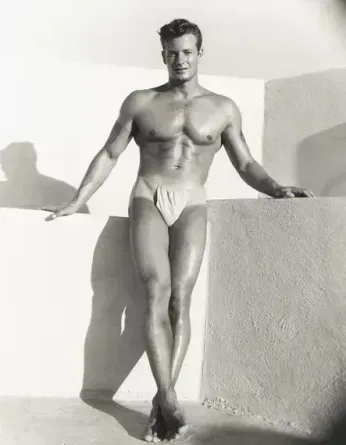

Considered the most prominent gay photographer of the male physique in the 20th century, Bob Mizer’s archives have been housed in the former Magazine shop in San Francisco’s Tenderloin district since 2016. Located at 920 Larkin Street, the Bob Mizer Foundation will soon change its name to the Bob Mizer Museum and Photographic Archives, but continues its mission of archiving and preserving the hundreds of thousands of images and films made created by Mizer.

Bob Mizer (1922-1992), who was born in Hailey, Idaho, lived in Los Angeles during the heyday of his career in the 1950s, and endured some legal difficulties over obscenity laws when he used the Postal Service to send photographs and magazines to fans across the country. He was jailed for taking photos of a 17-year-old model. He was later arrested by the Los Angeles vice squad for running a prostitution ring.

Thom Fitzgerald’s docudrama film “Beefcake,” released in 1999, told the story of his life, and although Mizer was for a time a success with his Athletic Model Guild, he did not live long enough to see how extensive his influence would become to male imagery, particularly in homoerotic arts.

To counter that cultural absence, the Bob Mizer Foundation continues to work toward preserving Mizer’s collection. But the story of how it ended up in San Francisco is a fascinating one as well.

On a recent visit to the foundation, President Dennis Bell and archivist Maxwell Zinkievich shared the intricate process of storing, filing, digitizing and preserving the films and photos of Bob Mizer.

Strike a pose

“When I acquired the Mizer estate in 2003, I knew that it was about to be sold off into pieces by Wayne Stanley, who owned it and had worked for Mizer,” said Bell. “It would’ve ended up all over the place, and maybe even a dumpster.” Stanley’s home was stuffed with the remains of Mizer’s archives, in some areas almost rotting from neglect.

“I’ve always been someone who thinks that family histories and their estates should stay together as much as possible,” said Bell. “So that’s kind of where it started; just trying to keep that estate together and keep it organized and eventually make it accessible for research.”

Bell, who said he considers himself a self-starter with many projects, is a former bodybuilder who already had an appreciation of vintage physique photography. In 1997, he started a website called PosingStrap.com.

“The internet was super young and I created a membership site because I was really interested in the old historical bodybuilding photos,” said Bell. “As a bodybuilder, I had competed, and really liked the old golden age of bodybuilding. I made a photographic membership site with that type of content. There was nothing else like it on the internet at that time, PosingStrap.com was the first. Eventually, I learned where these different estates of the bodybuilders had landed and who the photographers were. That’s what led me to understand and find the estate of Bob Mizer.”

By 2000, he’d met and befriended Bob Mainardi and Trent Dunphy, co-owners of The Magazine on Larkin Street, where the Mizer gallery and archives currently reside.

“I had gone in there many times looking for bodybuilding photographs that I could use on the website, that kind of thing. I got to know them, we became friends. We had the same interests. They had a huge treasure trove of photographs and everything they had collected over the years, including their personal collection. We just became good friends.”

Collectibles

In 2016, Dunphy and Mainardi met with Bell and decided to donate their entire collection and their building.

“The promise was there that they’d donate all of that to the foundation that I had established back in 2010, and the building to house it all,” said Bell. “They were making their own estate plans for when they planned to close The Magazine for retirement. They decided that’s what they wanted to happen with their collection.”

Bell moved the Mizer estate to his El Cerrito home in the spring of 2004 and started organizing and worked through it to learn about the intricacies of the collection. He opened an LLC named after Mizer’s Athletic Model Guild, and paid off the Mizer estate in installments over several years. He founded the new 501(c)3 nonprofit in 2010, and eventually began moving boxes into the upper floors of the Larkin Street building in 2016.

“During all those early years in El Cerrito, volunteers would travel from San Francisco to help me catalog everything,” said Bell. “And some of those people are still with me today. And now, we’ve switched places and I travel to San Francisco and the volunteers don’t have to travel as far. This has been going on for a long time. Eventually, we expanded into more space on the second floor at Larkin as the collection grew. After Bob Mainardi died in 2022, Trent knew it was time to close The Magazine.”

“Their business never really came back after the pandemic,” added Bell. “There were days when nobody came into the bookstore, so we decided it was time to transition and started getting rid of or moving out all of that magazine inventory they had, and getting the retail floor ready to turn into the current photographic gallery.”

Renovations

When asked about the beautiful wood shelving on the first floor, Bell offered some history.

“Bob and Trent did that,” he said. “They bought the building in 1989, after the earthquake. They spent years remodeling the entire building, which was built in 1925. They wanted to bring it back to that period look. The first floor was built as an optometrist’s office, and the guy sold glasses in the front and worked and ground glass in the back part of that first floor. Two apartments were up above. I think his mother lived up there.”

Bell continued, “The lower cabinetry is original, and Bob and Trent had more of it made to become the upper cabinets. They had that milled to match the original, and then had it all refinished. You can’t tell the difference between what’s original and what they added.”

Parts of the current mezzanine metal shelving and flooring came from the Bancroft Library in Berkeley.

“They carved out that whole area,” said Bell. “The stairway to the basement was originally in a different location on the retail floor, and they pushed it to the back corner and then built that metal staircase that goes from the basement all the way up to that mezzanine area. So that’s all from Berkeley.”

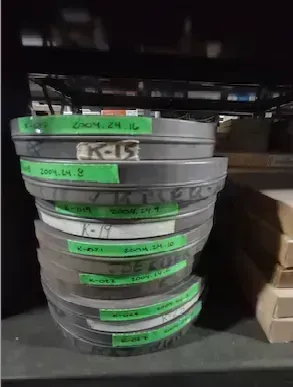

The sheer amount of items stored on those shelves is astonishing. According to Bell, the Mizer collection includes 400,000 4”X5” format negatives, 700,000 35-millimeter slides, 2,800 different 16mm movie titles and corresponding film negatives, and inter-negatives that were transferred to 8mm; more than 8,000 reels of film. The library holds about 35,000 periodicals, many quite rare, and 6,000 books. Most of these are photography monographs of the male nude.

Paging hunks

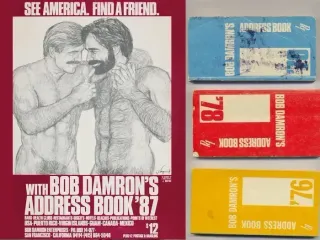

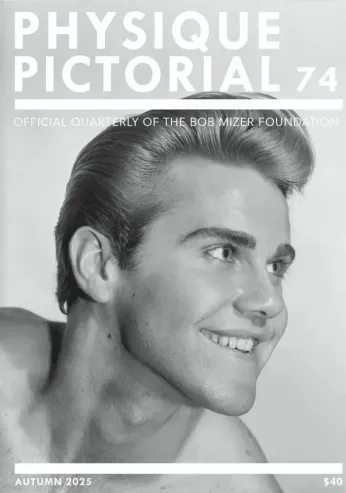

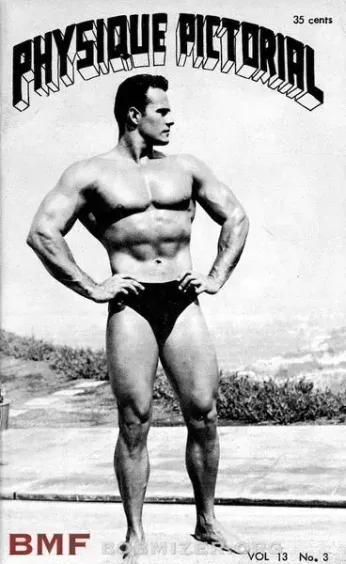

The Mizer Foundation is supported by memberships, ranging from $75 to $1000 annually, as well as donations. Membership benefits include free admission to the gallery events and talks, and copies of the quarterly “Physique Pictorial,” an homage to Mizer’s smaller-formatted magazines, which are now rare and valuable collectibles.

The new quarterly magazines include portfolios by modern photographers as well as curated vintage imagery by Mizer and his peers. Now in its 73rd edition, some back issues are also on sale at the gallery.

While Bell serves as Editor-in-Chief, the publication’s Creative Director Frederick Woodruff fields submissions.

“Many of the submissions we get are not really what we’re looking for,” said Bell. “We get a lot of nudes in front of a hotel room window or bed, and it gets tiring. The main thing with new photography is that we’re trying to keep it in Mizer’s theme as something that he would’ve published, but also without trying to be “retro.” We try to keep that in check. And it’s really important to show a younger generation where this stuff all came from.

“We also include essays, and have brilliant staff writers, like Corbin Crable, who writes for almost every issue. Keith Foote researches biographies and manages archival efforts. Some of the editorials can be anything from studies on different photographers or models or just different facets of early gay culture. It’s well-rounded. And we also feature artifacts from the Foundation’s Permanent Collection.”

A recent Kickstarter campaign supported the purchase of the digital film scanner at the archives.

“There are plenty of films that are in good shape that we’re able to scan in-house,” said Bell. “We’ve got the tools and volunteer help to be able to do that. A lot of other films that are older and maybe a bit more fragile need a little physical restoration, and we have a lab that does that for us, which is very expensive. Like any non-profit, funding is a huge hurdle.”

Bell credits members and donors with keeping the project alive. The Speaker Series and Film Screenings programs and gallery exhibits have welcomed a variety of audiences and scholars since October 2023.

“We’ve got some wonderful supporters who’ve been with us for years who diligently pay their dues. Other people just make straight-out donations,” said Bell. “We have a Naming Opportunity program, and the generosity of Jim Williams in Dallas has led to naming three spaces at the Foundation, including the Charles Longcope Jr. Photography Research Archive, named after his husband.

"All of this pays for the printing of the ‘Pictorial,’ helps buy archival supplies, and keeps the lights on. In addition to the gallery, and our mission is to show new photographers’ work, and make everything accessible in the archives so that it’s there for research.

“We get a lot of people searching for resources for all different research reasons, and we want to be able to make what we have to offer more accessible,” Bell added. “We have excellent and skilled volunteers who organize, catalog, and transfer the works into better archival housings.”

Storage and digitization

As he led a tour of the building, archivist Maxwell Zinkievich explained the procedures required in preserving the Mizer collection.

“Film is a very fickle material,” he said. “It degrades quite easily, quite quickly. Thankfully the archive is solely comprised of safety films. We don’t have any nitrate or anything like that, so it’s less of a flammability hazard, less toxicity, but it’s still a really fragile material.”

Zinkievich pointed to one of several temperature monitors on a wall.

“We’ll know if the temperature fluctuates too much or if the humidity fluctuates too much. While it’s not perfectly ideal in this situation, because of where we’re situated in San Francisco, the temperature and humidity stay relatively the same.

“Contrary to a lot of belief, the actual safest way to store film is on film,” said Zinkievich. “If you think about the last 30 years, how many different movie file formats have we gone through? We did VHS and DVD, and then we had some digital types of files, and those change quite frequently. There isn’t yet an archival final storage system.”

Added Bell, “Most of the work that’s done here is by skilled volunteers who focus on their own archiving projects. We’ve worked with universities to inspire people to come in for internships, work with material, learn how archives work, learn how a museum or a nonprofit on this scale works as well. Full-time paid staff is still something that we’re working through fundraising avenues to secure for us. We’re in a constant battle as nonprofits understand.”

Miles of files

The foundation’s purpose is threefold; preservation, archival, and exhibitions.

“We’re holding them in perpetuity,” said Zinkievich. “In our film lab, we go through and clean the films and then digitize them into 2K or 4K, depending on the element. We also get a really good look at exactly what the element is. We can rank it and put it into the database in certain different levels; if it’s in dire need of restoration and cleaning, or if it’s actually pretty stable. We have a backlog database of what the archive actually looks like and how the films are. And that’s an ongoing process, with thousands and thousands of reels.”

Archival scans of films are not retouched, color-corrected or changed. Zinkievich estimates that they have more than 550 miles of film, “which is just long enough to reach from our headquarters here all the way down to Mizer’s original studios in Los Angeles.”

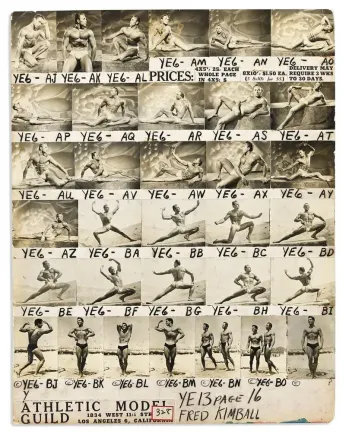

Mizer himself is known for his encyclopedic categorization of his model’s prints and films, including his own obscure code of hieroglyphic-styled symbols. The foundation’s current archival system is a bit more factual.

Of the actual films, Zinkievich said, “It’s best to digitize the films and then just play the digitization. Because putting a really fragile film element through a projector is not good. The projector is quite a violent apparatus.”

Zinkievich showed film cannisters and their original labels, and newer plastic cannisters that are among the films that have been digitized.

“What’s really interesting is we don’t just have completed films from Mizer,” he said. “We have basically the entirety of his workflow. We have the original negatives. We have original outtakes and clippings that were not included in final edits. We have those original first masters and then we also have multiple stock copy duplicates.

“And there are just stock copies that would’ve been sold to fans. These are unsold 16-millimeter stock copies. And then we even have the eight-millimeter inter-negatives, which he copied down to eight-millimeter to sell them for cheaper, basically. We also have all of those paper materials, so even if we don’t have an original master, we’ll probably have some stock copies.”

“Mizer saved everything,” Zinkievich added. “A film sometimes didn’t make it into the final cut, probably in a lot of cases because a model’s dick fell out of the posing strap, so he had to cut that out. But he saved everything. We had these boxes of just loose clips. Sometimes it’s only a foot long, 25 frames or longer, that didn’t make it in. There’s sometimes there’s B-roll of them just kind of goofing around on the side, the behind-the-scenes stuff and a lot of surprises in there. Nobody’s ever seen that stuff.”

Fortunate funding

Despite the current arts funding crisis locally and nationwide, Bell noted that the Mizer Foundation has received financial support.

“We worked with some really generous local funders like the Horizons Foundation here in San Francisco, others who generously supported our programming and as well as setting up the film lab and acquiring funds for that,” he said. “The National Film Preservation Foundation has also been instrumental in helping us. We have the equipment to basically do every step along the way, except to print new celluloid copies.

"So, we work with local film labs to get that done. And they’re always very kind and they understand the importance of the material that we’re working with. I don’t think that we’ve ever actually run into any big issues. Mizer never produced anything that at least I would term pornographic. We never see any real sex acts, just simulated sex acts as the laws were redefined later in the ’70s.”

Zinkievich said a goal is to eventually make such rare footage viewable for fans and members, including his color films.

“The earliest films we have from him are in color, and in 16-millimeter because he possibly thought, ‘Oh, it’s going to be a big thing.’ But very quickly, he realized that early ’50s color film on this sort of scale is not really worth it. So, he moved onto shooting in 16-millimeter black and white, usually with no sound. Most of the films we have here are black and white. He would sell them as 16-millimeter for quite a while.”

Home viewing

It’s fascinating to imagine the legion of fans buying projectors and films.

“It turned out to be a high-end luxury product coming out of AMG,” said Zinkievich. “We did inflation adjustments for the cost of some of these films and some of them are $60 to $100 a reel; quite expensive. It wasn’t until the 1960s when he took some of these older films and stepped them down to eight-millimeter.”

Mizer’s original home movie screenings are described by Zinkievich.

“He would throw small events at the AMG studios,” he said. “He would invite well-known clients of his that lived in the area to come in and basically see what he shot that week. Some of them were big customers, some of them were models. He would screen films depending on what they were interested in seeing.”

Zinkievich described the modern version at the foundation’s gallery.

“We have held monthly film screenings that were free to the public, just anyone could drop in. It’s interesting. What does the audience think of these films? How has the perception of them changed over the course of their lifetime? What do they look like now to a contemporary audience?”

While some of the costumes –a few of which are still in the collection– may carry an antiquated or culturally appropriative burden, the films do retain an air of innocence amid the nudity.

“Throughout Mizer’s material specifically, in comparison to other physique photographers like the contemporaries, Mizer always has this sense of whimsy, of not taking himself too seriously, of allowing the audience to relax and not be caught up in the pretense of it. There are always smiles on the models’ faces. It’s always about joy in a lot of ways. I think that lends itself to really being able to enjoy the material. You’re always invited in by it. It could be super voyeuristic where the model doesn’t know the camera is there. He’s constantly inviting the viewer into the material and to connect with the model, connect with the person.”

Zinkievich summed up, saying, “We at the foundation understand how important Mizer’s material is. His legacy and this work are not only important for the history of erotica, but also for the history of queer men’s identity and understanding, showing that it still exists in this beautiful, fun, joyous way and isn’t necessarily something that we all need to be afraid of. And that sort of visibility and legacy is something that is palpable and seen in the material.”

The Bob Mizer Foundation’s current exhibit, ‘Stuart Sandford: In Youth is Pleasure,’ through Nov. 29. The next speaker series, ‘Spanko! AMG and the Rise of the Spanking Community,’ a panel with Justin Stephens and a screening of Mizer’s short films, $10, Sept. 25, 7pm. 920 Larkin St. Gallery open Tuesday-Saturday 12pm to 6pm and by appointment.

https://bobmizer.org/